Integrating with third-party vendors – what can go wrong

Photo by Sarah Kilian on Unsplash

Things are bound to go wrong when integrating two systems, more so when one of these systems belongs to a third-party vendor that you have no control over. I have experience with integrating vendors and managing these integrations. I am ranting here about the common patterns I have noticed in such integrations.

What you see is NOT what you get

You have integrated with the vendor, and the tests are passing. Everything looks good until you start getting reports from customer service that some of the users are seeing weird characters in their names. Jöhn Doé becomes J�hn Do�. We all have seen these characters at least once on the Internet. These characters appear when strings encoded in an encoding format are decoded with a different and incompatible format. Most of the time, we deal with UTF-8 which is a common text encoding format. However, there are legacy systems that use other, close but not quite the same standards. The bigger and older the vendor is, the higher the probability of them using an obsolete text encoding standard.

In my experience, most of the time, it ends up being a windows equivalent of popular standards, like windows-1252 for ASCII, and UCS-2 for UTF-16. I won’t try to explain the differences between these encodings and why they exist because it will only give a false impression that I understand them; I don’t. Hence my encoding of choice is WTF-8. Enough rant about encoding; coming back to the topic of vendors. Large vendors using Windows or IBM servers are likely to use these less popular encodings. So it is always good to clear that out with them.

Log ‘em all

The vendor system integration has been deployed and running successfully for a while. Suddenly you get paged that your system is behaving unpredictably and causing issues in the vendor system. You can not see anything wrong at your end and ask for logs to determine the issue. To your horror, the vendor does not keep logs, and you are on your own to fix the issue or prove there is no issue to begin with. To avoid such a scenario, I encourage logging more than required. All the points where control flows from your code to an external entity or the other way around should have excessive logging. Example:

1 | 2021-09-12T10:29:32.387Z [info] (api.js:5): Sending data to vendor X {"url":"https://vendor-x.example.com/system-y","data":{"tickets":[{"userId":"4567899","count":2,"date":"12/09/2021"}]}} |

Example of logging everything that goes out or comes in.

Duplicate requests are coming

You have just started your week on a Monday morning with a cup of coffee when you notice that everything in the system is happening twice, and sometimes thrice. Some services are constantly alerting because they can not process duplicate events. Most of the time, these alerts are good. The problem is the services that are processing these duplicate events instead of alerting. This could lead your communication service to send multiple emails to customers or the billing service to charge the consumers more than once. Hours of debugging later, you hear the news that the vendor found the issue in a new version was released last weekend with a botched retry system.

The solution to this is building idempotent systems which can process duplicate events gracefully. While idempotency will allow your systems to stay afloat in a situation like this, the excessive logging we added in the previous step should help in debugging and communicating to your vendors.

1 | 2021-09-12T10:54:14.261Z [info] (api.js:6): Request received from vendor X {"route":"POST /tickets","checksum":"e4608c43cfeede8f0ccd0f770305ec01b94ba554d72b7ff8a6e659bfdf6727a9","data":{"tickets": {"userId":"4567899","count":2,"date":"12/09/2021"}]}} |

Example of ignoring duplicate requests based on checksum

Concurrency is a privilege

Modern APIs and systems are web-scale, that means they can handle multiple sessions, requests, and processes at the same time. This is called the concurrency of the system. Generally, banks and other financial institutions limit the number of concurrent sessions by the same users to one. This could mean different things in the backend. Good APIs have well-defined limits on this concurrency and throw expected errors when this limit is breached. Poorly designed APIs have unclear limitations on concurrency and can result in undefined behavior on their breach.

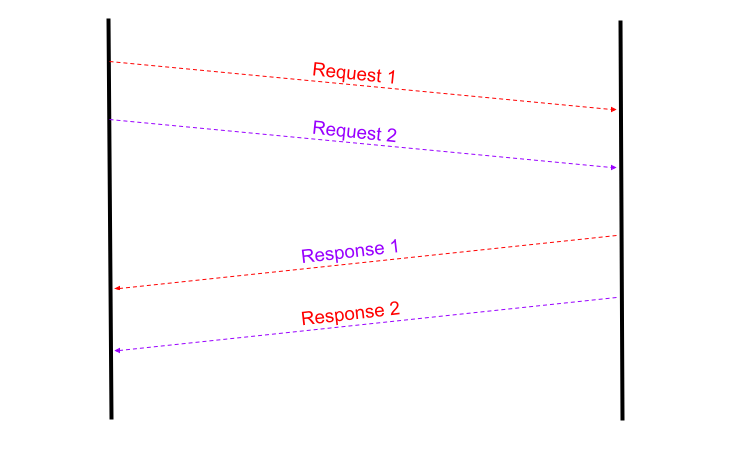

One such situation which left me doubting everything was when a vendor could not handle multiple requests at the same time and it would often mix the response of two requests. It sent the response to one request in the channel created by another HTTP request.

Response 1 is sent in the channel created by Request 2 and vice versa

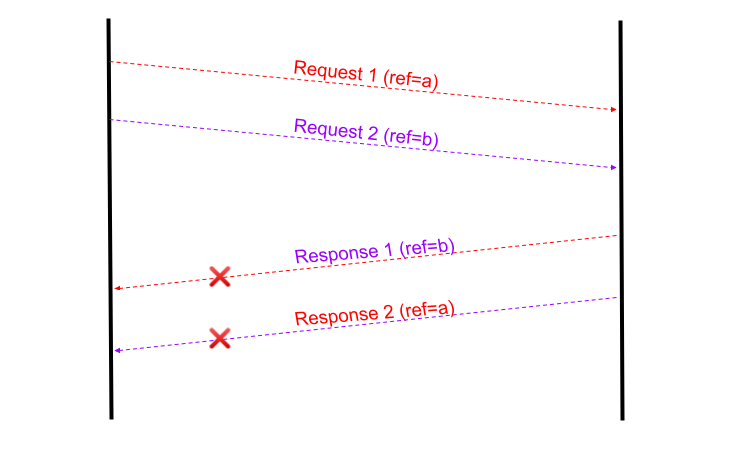

What I found helpful in a situation like this is tagging the requests with a reference. If the vendor system can echo back the reference sent in the request along with the response, it could be used to identify the discrepancy.

Matching the ref sent in request (a) with the one in response (b) helped identifying the issue

Firefighting the firewall

You just got hold of the endpoint for the vendor system, and you hook it into your application. It should work as-is, and in most cases, it would, but sometimes it would not. You would confirm with the team on the vendor’s end if it’s a firewall issue, but they would say it is not. At this point, you will start exploring everything, including the TLS version, self-signed certificates, network timeouts, keep-alive header, loadbalancer issues. You get the picture. You ask the developer team of the vendor again and this time they escalate your issue to the network team, which says, of course, it is the firewall.

Photo by David Pupaza

Some firewalls require whitelisting of IP addresses, which would require you to get hold of “permanent” IPs like AWS Elastic IP addresses. After your IP addresses are whitelisted, it should be good to go. Some firewalls are configured to strip some headers, making you wonder why your requests are ending up as “unauthorized”. Figuring these issues could be hard if there are not enough logs and communication between the teams.

Parting notes

Well, I may have painted a grim picture here, but it’s just a rant about all the things that can go wrong (and have gone wrong) when integrating with external systems. Things are rarely this bad if there is good documentation. I hope reading this will prompt you to ask more questions when you integrate with your vendor and save time.